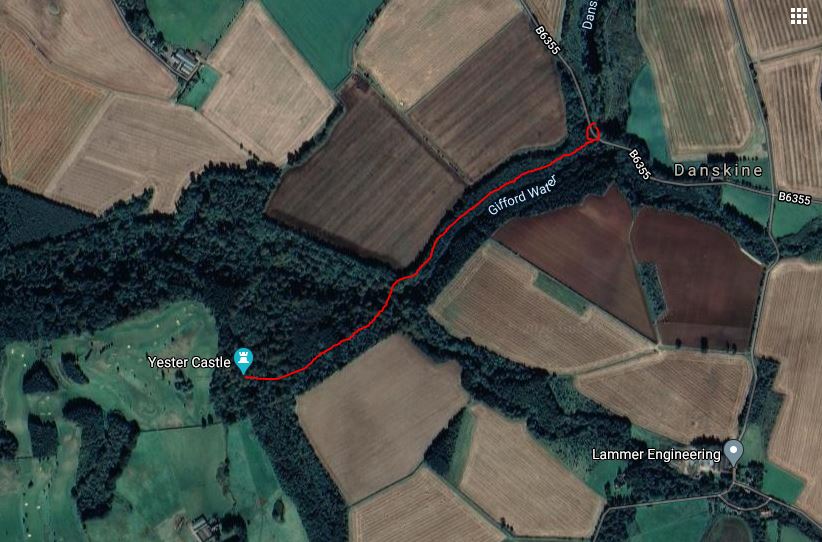

Its been a frantic few weeks in the world of Walking East Lothian. After spending the year cavorting with my dog Daisy about the county, I realised that walking other people’s dogs around the same places could be a nice way of making a wee wage. The result is Fetch! East Lothian, my transcounty, council-approved, fully-insured, dogwalking service. So far we have three ‘clients’ – the dog in Musselburgh has open’d my eyes to the amazing Levenhall Links, which we’ll be covering in this blog early next year. There’s also a couple of rescue dogs in Gifford, which means we get to enjoy Yester’s amazing woodland regularly.

So, to Circlin’ Kilspindie. The name relates to the golf course on the western fringes of the spectacular seagirt settlement that is Aberlady. Of this wonderfully airy, breathy & scenic village, Rev John Smith wrote in the 1845 Statistical Account of Scotland, ‘Aberlady does not appear to have been the scene of any memorable event, nor is it famous in history as the birth-place, or place of residence, of any very eminent men.’ This is a rather staid approach to history, however, & I found the walk I took in the area with the wife & Daisy absolutely fascinating.

We settled the car on a scintillating morning by a small public park called The Pleasance, opposite a kirk on the extreme western outskirts of Aberlady, just off the coastal road. The kirk in question is the Aberlady Parish Church, dedicated to Saint Mary. Dating from the 15th century, it was re-built in 1887 – designed by London architect William Young – and was described in a newspaper of the time as, “one of the finest ecclesiastical buildings in Scotland.”

On this occasion we refrained from entering the kirk’s cloisters, & instead follow’d a path around its grounds & thetwo peaceful graveyards to our left. The path then dives directly forwards toward the Forth. In a field to our right we could make out the clump of trees & ruined brickwork that mark the site of Kilspindie Castle. An early fortalice of the Spens family, it was destroyed in 1548 by the English during their occupation of Haddington, enabling English supplies to be landed unchalleng’d.

Our path soon reach’d a more pristine pathway, which we took to our left, soon arriving at the main hub of the Kilspindie golf course club. Just before the clubhouse itself, there is a building which I sensed was the ‘Town of Haddington’s House,’ from which the county town handled its imports & exports. Aberlady was an important harbour for fishing, sealing, and whaling and was designated “Port of Haddington” by a 1633 Act of Parliament, helping maintain Haddington’s burh status with enhanced overseas trading privileges.

There has been considerable alteration on the coast at Aberlady Bay since these old times. The sea has made great inroads into the coastline around Kilspindie Links. The course of the Peffer Burn has also been getting gradually shallower, & at the Point, where the ships used to anchor, the foreshore presents to the older inhabitants quite a different appearance to what it did in their own recollection

John Pringle Reid: Historical Guide to Aberlady (1926)

From this vantage, the view of Aberlady Bay’s fabulous nature reserve is lovely; over the Peffer estuary & onto the rolling Gullane dunes, with the sky offering the occasional puffs of blunderbus-blasted flocks of wintering Geese.

The rough remains of the old port’s anchorage protruded from the clay bottom, upon which in former days boats rested safely when the tide was out. One famous local legend is that of fisherman Skipper Thomson, the pilot at Aberlady, who was unfortunately lost in a storm. Not long after his disappearancem his wooden leg washed up nearby, & was dutifully handed to his widow, who kept it on her mantelpiece to her dying day.

The port’s decline began with the coming of the North British Railway in 1846, with a station opened at Ballencrieff. The townsfolk were canny, however, & the year before the railway was officially opened in the area, they hold sold their rights of anchorage to the Earl of Wemyss. It was the same guy, by the way, he restored the parish kirk in 1886.

The quaint clubhouse of Kilspindie Golf Club, which possesses a rich history. Formed in 1867 as the Luffness Golf Club, it was the 35th registered golf club in the world, with the course then was on the far side of the Peffer Burn on land which is now part of the Nature Reserve. Unfortunately for the historian or enthusiast, there is little evidence of the course layout and the original clubhouse.

A few years later, there was a split in the club, with some members moving to a new course nearer Gullane, & others to the links land Craigielaw Farm, & named Kilspindie in 1899. Of this new course – which has hardly changed in 112 years – one of its first members, Ben Sayers (see our walk along North Berwick Beach) commented, “one would almost think nature had intended this for 18 holes as there is just sufficient ground and no more.”

It was time to commence proper our circumnavigation of Kilspindie Links, a fond daunder by the seashore with the wife & dog, perched upon a sliver of coastal path between the soft golf turf & the shelly sands that edge the Firth of Forth. Guided by short, white, stubby poles, we found ourselves traversing the 2nd & 3rd holes of the Kilspindie course, happy to have be born into a world which offers such walking as this!

Half-way down the third fairway, just as we were passing an ornithologist building, the weather abruptly changed. ‘This wasn’t predicted‘ cried a golfer in near despair at the green, huckling behind an imaginary shelter in his mind as he braved his putt.

Not long after the birdwatching house, we descended to the beach itself. It was quiet, secluded, & gorgeous – no clanking clubs & yelps of frustrated golfers disturbing the natural peace here! The coast was startlingly refreshing visually, with very handsome rock formations pleasing the eye; while out to sea an oil tanker sat idly on the sea, obscuring for a moment the eyeliner-like illusion of a dull sky, doubling over, darkening the sea. All-in-all a perfect painting & a total gorging of East Lothian-ness.

As we reache’ the end of this comfortable stretch of beach, we surmounted once again the links, & found the wind picking up & the rain falling harder as 45 degree jagged bolts. Poor Daisy, she’s not a fan of this kind of thing, but like the golfer I was also completely surprised by this extreme turn in the weather.

We soon reached another beach, a real natural gem which reveale’ an expansive & succulent panorama. In one sweep of the eyes one can make out the phantasy of Fife, individual details of Edinburgh Castle, the towering apartments of Newhaven, the mound-whales of the Pentlands & even the hoary Ochils far out to the west.

At the end of this beach one arrives at a large, whitewashed empty building in the vicinity of ‘The Quarry’ – i.e. the 9th tee of a second Golf Course situated on the Links. This new club is called Craigielaw, whose Championship links course was designed by Donald Steel & opened in 2001.

From the tee we found a road, a few meters along which we then turn’d left into the relative shelter of some woods. Thro’ the trees to our left we could see the large houses of Craigielaw Park – one of those rare British conurbations that are the ‘gated communities’. ‘They have many in America,’ explained the wife, but in Britain they haven’t really taken off. Still, having keypad-only-access to one’s cul-de-sac does help to justify spending the million pounds or so that these houses cost – alongside, of course, the kitchens by Clive Christian.

Back in the woods were were getting colder, & the wife was carrying Daisy for large spurts. Not only the cold, but the finally leafless trees all were telling our souls that Winter was really here. Still, its a charming stretch of walk, with clear paths leading to a gate & a road.

At this point one is faced with two choices. Follow the road a little to the right where it joins the John Muir’s way, running parallel to the main road, or cut across Craigielaw’s driving range. As the weather had turned heinous, the range was empty & so we pursued the latter course.

On reaching the very convenient John Muir’s Way, it was now a simple stretch back to the Pleasance & the car. Just before reaching the relative warmth of our Renault Scenic, we came across the remarkable building that is the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club (SOC). It wasn’t the right time to enter – we were soaked – but I made a mental note to return sometime the next week to check out.

Finding myself driving through Port Seaton a few days later, I suddenly remembered both my pal, Gary Riley (originally from Elphinstone) & my fact-finding mission at the birdwatching center. A phone call & a wee drive later we were entering Waterston House – the aforementioned HQ of Scottish birdwatching. It is named after George Waterston, a one-time Director of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in Scotland, famously who pass’d his idle hour as a POW in WW2s twitching & writing birdwatching articles for the camp’s secret newspaper.

A lovely French lady called Laura took us under her wing brilliantly; explaining the history of the place, & showing us about like a courtesan receiving foreign dignitaries at the Sun king’s Fontainbleu. She is the curator & organiser of the eight, six-week exhibitions that the center holds every year in its gallery. These are definitively dedicated to Natural History, the duty to which is enshrined in the constitution drawn up by the society. 2019’s line-up is done & dusted already, she explained. For me & Gary in December 2018, we witnessed the explicitly vivid animal art of young & gifted Lucy Newton. I was blown away by her stunning squirrels, while Gary completely adored her shags!

The Scottish Birdwatching Center began life in the 1930s, when a group of adolescents set up their society, including George Waterston. Money began to pour in from enthusiasts & benefactors, & they were able to buy a property on Regent Street, Edinburgh. They sold this 14 years ago, & used the money to create this purpose-built center overlooking Aberlady Bay & its reserve. The center houses the largest ornithology library in Scotland (over 3,500 pieces), housed in funky mobile shelving units, which on the day of our visit was being used by a gentleman researching for his degree upon the habitats of Geese.

There is no cafe at the center, & Gary told me of the time a few months ago he’d gone riding on his electric bike, at the end of which he found himself at Waterston House. Feeling thirsty, & asking if he could buy a coffee, he was met with the reply, ‘you cannot buy one, but we can make you one,’ a quite congenial response!

To contribute petrol & petfood

Please make a donation

***

So god bless Rennie, & let us now take ourselves on a wee tour of the Yester Estate, currently in the hands of an Aberdeen oil family, headed by Ian Wood. Before the Woods, there was the Italian composer, Gian Carlo Menotti, who had lived at Yester into his 90s until 2013. At the age of 7, under the guidance of his mother, Gian began to compose songs, and four years later he wrote the words and music of his first opera, The Death of Pierrot. The Consul, Menotti’s first full-length work, won the Pulitzer Prize and the New York Drama Critics Circle award as the best musical play of the year in 1954. Flush with money from his efforts, he bought Yester in 1972 from two antique dealers who had bought the estate from the Hay Marquises of Tweeddale a handful of years earlier.

So god bless Rennie, & let us now take ourselves on a wee tour of the Yester Estate, currently in the hands of an Aberdeen oil family, headed by Ian Wood. Before the Woods, there was the Italian composer, Gian Carlo Menotti, who had lived at Yester into his 90s until 2013. At the age of 7, under the guidance of his mother, Gian began to compose songs, and four years later he wrote the words and music of his first opera, The Death of Pierrot. The Consul, Menotti’s first full-length work, won the Pulitzer Prize and the New York Drama Critics Circle award as the best musical play of the year in 1954. Flush with money from his efforts, he bought Yester in 1972 from two antique dealers who had bought the estate from the Hay Marquises of Tweeddale a handful of years earlier.

It is certain, that many of the trees are, by this time, of much more value than six pence a tree; for they have now been planted near three-score years. And tho’ it is true, that a firr-tree is but a slow grower, and that most, if not all the trees I speak of, are firr; yet it must be allow’d that, the trees thriving very well, they must, by this time, be very valuable; and, if they stand another age, and we do not find the family needy of money enough to make them forward to cut any of them down, there may be a noble estate in firr timber, enough, if it falls into good hands, to enrich the family.

It is certain, that many of the trees are, by this time, of much more value than six pence a tree; for they have now been planted near three-score years. And tho’ it is true, that a firr-tree is but a slow grower, and that most, if not all the trees I speak of, are firr; yet it must be allow’d that, the trees thriving very well, they must, by this time, be very valuable; and, if they stand another age, and we do not find the family needy of money enough to make them forward to cut any of them down, there may be a noble estate in firr timber, enough, if it falls into good hands, to enrich the family.

He is perhaps best known to fame as the instructor of King Edward, King George & Queen Alexandria. He first met King Edward six years ago, when the late British monarch was visiting North Berwick. The King sent for him, & after Sayers had shaken hands with the King, the latter asked him how the Grand Duke of Michael of Russia, one of his pupils, was progressing, to which Sayers replied, ‘I am sorry to inform your majesty that he was one of the keenest & one of the worst.‘ whereupon the King stroked his beard & burst out laughing. As a result he was summoned to Windsor & told to make the King a set of clubs, which he did. Later he gave Sayers a beautiful tie pin, which is one of his prized possession.

He is perhaps best known to fame as the instructor of King Edward, King George & Queen Alexandria. He first met King Edward six years ago, when the late British monarch was visiting North Berwick. The King sent for him, & after Sayers had shaken hands with the King, the latter asked him how the Grand Duke of Michael of Russia, one of his pupils, was progressing, to which Sayers replied, ‘I am sorry to inform your majesty that he was one of the keenest & one of the worst.‘ whereupon the King stroked his beard & burst out laughing. As a result he was summoned to Windsor & told to make the King a set of clubs, which he did. Later he gave Sayers a beautiful tie pin, which is one of his prized possession.

William entered St Andrew’s university whilst aged around 10 in 1475 to take his MA. In those days this level of education was roughly equivalent to that of secondary schools today. Thereafter he became a Franciscan novice and visited every flourishing town from Berwick down to the Kent coast and in the process preached at Dernton and Canterbury. He crossed from Dover to the then Picardy, to instruct, where possible, its denizens. He also ventured a good deal further West. He became an ambassadorial secretary for James IV carrying out diplomatic missions.

William entered St Andrew’s university whilst aged around 10 in 1475 to take his MA. In those days this level of education was roughly equivalent to that of secondary schools today. Thereafter he became a Franciscan novice and visited every flourishing town from Berwick down to the Kent coast and in the process preached at Dernton and Canterbury. He crossed from Dover to the then Picardy, to instruct, where possible, its denizens. He also ventured a good deal further West. He became an ambassadorial secretary for James IV carrying out diplomatic missions.

Of the graves checked out by me & Daisy, a few stood out, including quite a number of Napoleonic victims, such as William Norman Ramsay whose body was reinterred in the graveyard from the very fields of Waterloo. A rather interesting grave was that of the anonymous Mary; perhaps the illegitimate sister of a wealthy nobleman. Another was the impressive family tomb of Sir Archilbald Hope, who appears as a portly portrait in John Kay’s ‘Knight of the Turf.’ This classic Scottish Enightenment figure drained and cultivated a marshy piece of land south of Edinburgh – known today as The Meadows, but historically often referred to as Hope Park.

Of the graves checked out by me & Daisy, a few stood out, including quite a number of Napoleonic victims, such as William Norman Ramsay whose body was reinterred in the graveyard from the very fields of Waterloo. A rather interesting grave was that of the anonymous Mary; perhaps the illegitimate sister of a wealthy nobleman. Another was the impressive family tomb of Sir Archilbald Hope, who appears as a portly portrait in John Kay’s ‘Knight of the Turf.’ This classic Scottish Enightenment figure drained and cultivated a marshy piece of land south of Edinburgh – known today as The Meadows, but historically often referred to as Hope Park.

Just before the carnage began, a strange burst of chivalry burst out between the two armies; the death spasm, perhaps, of an age before gunpowder. The Earl of Home led 1,500 Scottish horsemen – mostly Borderes – close to the English encampment and challenged an equal number of English cavalry to fight. With Somerset’s reluctant approval, Lord Grey accepted the challenge and engaged the Scots, who were badly cut up and were pursued west for 3 miles. After this the Scottish cavalry was basically KO’d from the main fighting. William Patten, described the slaughter inflicted on the Scots;

Just before the carnage began, a strange burst of chivalry burst out between the two armies; the death spasm, perhaps, of an age before gunpowder. The Earl of Home led 1,500 Scottish horsemen – mostly Borderes – close to the English encampment and challenged an equal number of English cavalry to fight. With Somerset’s reluctant approval, Lord Grey accepted the challenge and engaged the Scots, who were badly cut up and were pursued west for 3 miles. After this the Scottish cavalry was basically KO’d from the main fighting. William Patten, described the slaughter inflicted on the Scots;